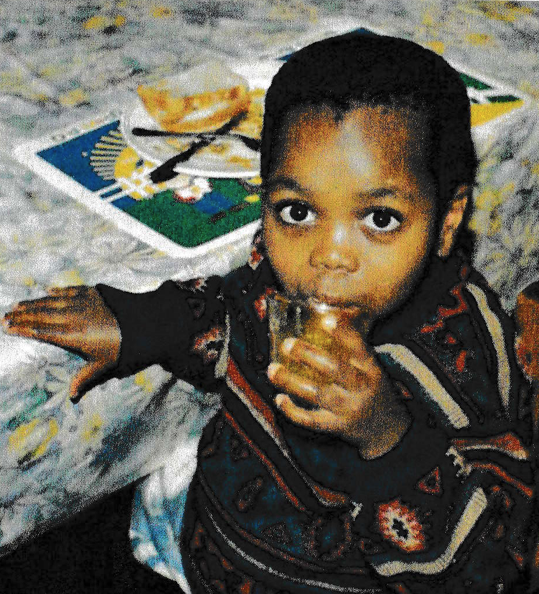

His name was Yibanathi Hliso and he was born on 4th September, 1989, in South Africa in the Eastern Cape, in a city called Port Elizabeth, at Livingstone Hospital. He died of the disease of AIDS on March 30, 2006, when he was not even 17 years old. I never had the pleasure of meeting this incredible young man. But I befriended his adopted parents, the Matthews family from the United Kingdom.

David and Joan Matthews are originally from England, but they lived in South-Africa for a long time. This is where they met Yibanathi, or: Yibi, for short. I myself got to know the Matthews family during my years in Bermuda (2009-2011), where I lived when my husband got a temporary job there. Even though Yibi was by then no longer with them, he was such an intrinsic part of the family’s identity, that meeting the Matthews’s without knowing about him was almost impossible.

Bermuda was the place where I discovered the art of watercolour painting. I have always been involved in the arts, and I was happy to become a part of a small circle of artistically inclined people on this beautiful archipel of islands. Watercolour, however, was a new medium to me. I kind of liked how unpredictable it was and how you can be surprised by the often unexpected results of your creations.

When I met Joan Matthews, we became fast friends immediately. David is a reverend in the Anglican Church, and we had the most interesting conversations whenever we got together for coffee or painting. I do not come from a religious background myself, but I do consider myself a spiritual person. So we always had lots to talk about, while enjoying a brew and some cookies. It did not take long for Yibi’s name to come up and I was so moved when I heard his story. Joan told me that she only ever had snapshots of Yibi and how she would love to have a portrait done of him. Even though I considered myself an absolute beginner in the watercolour technique, something in Yibi’s story resonated with me and I offered to give it a try. It was never an official commission, there were no deadlines and even no expectations. I would just give it a try. Yibi’s would be the very first portrait I ever painted…

Before I continue, let me tell you a little bit about Yibi’s journey in life.

He was the child of an African lady in poor living circumstances, who was unable to properly take care of him. She passed the HIV/AIDS infection on to him and in those years, even though more and more was known about this disease, it was extremely hard to find out how to treat it. Also, South-Africa was not exactly first on the list when it came to receiving new medications.

And so it was that Yibi was sick for most of the days of his short life, being handed off by his mother to his grand-parents, who did not know what to do with him. A long list of hospices and orphanages followed, with long periods in between of living in the streets. Ultimately, Yibi landed in a new institution for those affected by HIV/AIDS: the Resurrection AIDS Haven in Port Elizabeth. And this is where Joan and David Matthews found him. After a number of years they decided to foster him. And when they moved back to Great-Brittain, it was unthinkable to leave him behind – so they adopted him. And Yibi became Yibanathi Hliso Matthews. With Joan and David he finally got the chance to experience what it was like to truly belong and have his own family. He was a twinkling star who was adored by all who met him and will forever live on in their hearts. As one friend put it, after attending Yibi’s funeral:

“How could a heart, a passion and a love so big fit inside a wooden box so small?”

So how did he affect me?

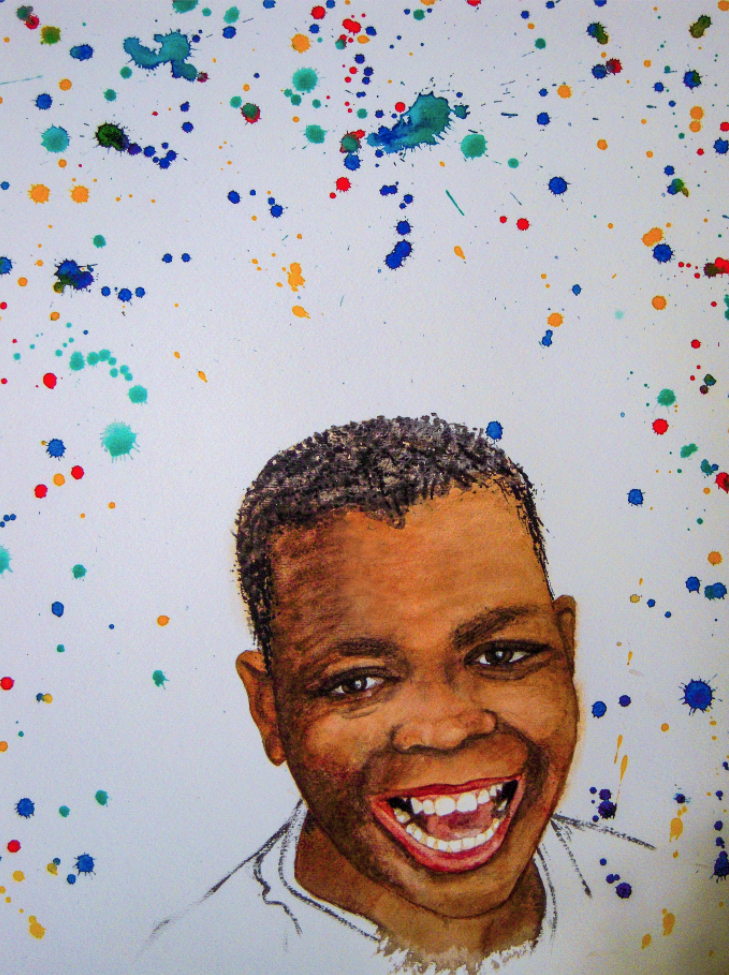

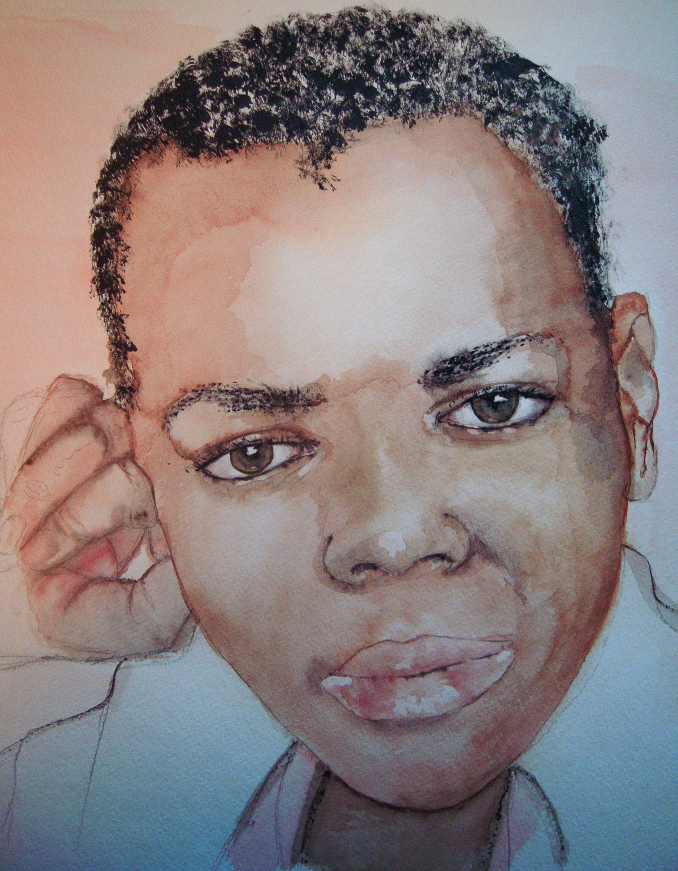

Well… the day I offered to try and do a portrait based on a series of snapshots, was also the day that I invited Yibi’s spirit into my home. As I studied his pictures, and even now, as I am writing about him, the hairs on my arms stand on end and a shiver travels up and down my spine. In Canada’s winter, it is not odd to get the shivers, but in Bermuda temperatures are subtropical and being cold is not really something you would expect to happen to you. But it happened. I took out my painting materials, sat at the dining table and started to dabble. After a couple of tries, I produced a realistic portrait of a young boy with a dazzling smile. I was happy with the result. Especially considering how little experience I had, at the time, with the medium of watercolour.

So… the job was done. Right? Wrong.

As I was walking around in our little house, something kept me from putting away the painting materials. At first I ignored this reluctance to clean up the table. But as the twinge to sit down and keep painting kept coming back, each time I walked by my painting tubes and brushes, it was harder and harder to ignore. I had also started to become aware of how cold I got, every single time I walked by the easel with the first portrait. It was really quite odd.

It felt in a way like being invited to participate in a game. I was not cold the whole day, but I got the shivers whenever I was close to my painting stuff. I decided to ‘play’ and gave in and started to draw a second portrait. There was just a loose likeness to Yibi. I did not seriously think that anything would come of it. The spontaneous painting process was also completely foreign to me. The first portrait was really a planned copy of one of Yibi’s photographs.

A completely different result…

But I did not really have an exact reference the second time around. And the process of painting was completely different from before. It was loose and unpredictable. There was more water than paint. There was liquid movement that I had no control over. It was quick as well. Much quicker than the first portrait. I was quite enamoured with the result, to be honest. But I did not think that this was what Joan and David wanted. I would just keep it, if they did not want the second portrait.

When the Matthews family came over, they immediately took to the first portrait, as I had expected. Then I told them:

“Yibi actually ‘made’ me create a second one. It is very different and you may not like it and that is perfectly fine… ”

When I flipped over the page and showed the second portrait, it did not resonate with them. This was not a portrait of the pre-teenage boy that they had engraved in their memories.

So we had another cup of tea and chatted about this, that and the other. And then I caught both of them stealing glances at the second portrait. Long story short: they wanted both of the portraits and in the end liked the second one best. They reasoned that it perhaps showed Yibi as he would have looked, had he had the chance to become an adolescent, a young adult. I think this was the biggest compliment I have ever received about any artwork I have ever made.

As they left the house with the two paintings, I brought up the subject of my shivers. And how I felt they were connected to Yibi’s presence in my house. Without missing a beat, David opened the backdoor of his car and urged Yibi to come along with them. “Come on now, Yibi, leave Nicky alone!” Threw me a big grin and off they went, back home.

The shivers never came back. Unless I tell his story. And that affects me deeply. Yibi wrote a little book about his life. His narrative is not that of a teenage boy, let alone a child. It is the story of how he experienced his life in an astonishingly mature way. And even more pointedly: how actions of other people made him wonder about his disease in particular and the world at large. No body-pains could ever keep him from enjoying life to the fullest. To see snow for the first time after he moved to England was a miracle to him. He turned into a true entertainer for those around him, making them burst into giggles. And attracting the attention of many a girl as well…

Here is some of what he wrote about his disease:

How to stay positive

“I couldn’t do all that the others could do, which [often] upset me.

Sometimes I feel disappointed that the doctors promised me things that I have not been able to do. I was really happy when they said that I would be just like [other people] even though I would still have the virus. They said I could live until forty, that I would be strong and independent, that I would grow into a man, have a wife and kids. But now that has been taken away from me, I feel very sad and cross.”

“I know it is hard not to just forget about life because you think that once you have HIV your life is over. I know that you are scared and worried that you will die and you don’t think that anybody can help you or would even want to help you.”

“I am going to tell you about how you can be positive even though you have this disease, and try to enjoy life despite the disease. […] The reason I have been able to live with the virus for so long is due to a series of fortunate circumstances and the fact that, due to knowledge about the disease, I have been able to have a very positive outlook.”

“The reason why I know so much about HIV is that in Africa, the land where I was born, it is so much a part of life that people have given up. Parents, especially white parents, keep it a secret from their children and think it won’t happen to them. The schools do not educate the children about the disease because they are not allowed to by the parents, who still tend to think of it as a black or homosexual disease. Children do not need to dwell on it, but at least they would have better understanding about it and be able to protect themselves against it.”

“You shouldn’t have more than one sexual partner and wearing a condom can help reduce the risk of catching HIV. You must also be careful when touching someone if they are bleeding, as the virus can be passed on through the blood. For example, if both people have cuts on their fingers, the blood must not mix.”

“Having HIV does not mean that you can’t hug someone, kiss or shake their hand. Having HIV does not always mean you look unwell; it doesn’t show that you have got it. People can look at you and think ‘He’s perfectly alright’.”